During the past few days the world has been rocked by the terrorists attack on Charlie Hebdo magazine in Paris, a tragedy that has brought France its most large scale violent attack in two decades and fueled the ongoing debates around the notion of freedom of speech. The general argument, in this instance, has suggested that Charlie Hebdo is the brave crusader which has had its voice suppressed through an act of terrorism. Indeed, this argument is a valid one. However, in considering this incident and its consequences, I think it’s necessary to take note of the other side of the coin: the religious voice and its place in freedom of speech.

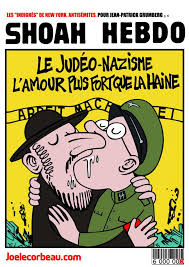

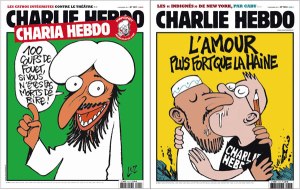

It has to be stated that many of the issues of Charlie Hebdo in the past couple of years have gone beyond acceptable bounds of extremity. In the magazine covers below, both the Muslim (via the Prophet Mohammed) and Jewish communities are represented in ways which are (for lack of a better word) problematic:

“Discomforting” and “inappropriate” are probably the kinder words that emerge when viewing these images for the first time. Yet, despite this, there is a significance to these images. Whatever our emotional response to them, what they encourage is a process of critical thought that challenges us and, perhaps, even makes us examine the depicted situation from a different perspective. The problem is that this form of freedom of speech, as important as it may be, almost always encourages active antagonism towards religion. The message is “religion destroys”, “religion kills”, “religion oppresses”, “religion works against freedom of speech”. Indeed, it’s hard to find a way through which to defend religion when it’s considered the very medium that stops us speaking about it. Many will now claim that the attack on Charlie Hebdo endorses this statement.

Here’s the thing though. For me, religion is not what oppresses freedom of speech. Rather, it’s the way that it’s approached, interpreted and utilized that prevents any dialogue from taking pace. Two Islamic terrorists do not speak for the religion in its entirety. What they ultimately symbolize is an idea, one that they have extracted from but is not necessarily embedded in the religious values they claim to represent. Whether it be the Torah, the New Testament or the Quaran, an understanding of a religious text is shaped not by what it says but how it is read. The problem is that public discourse latches onto particular figureheads who represent a textual reading that is more temperamental, more combative, one that is more easy to oppose than engage. That then becomes the dominant reading. There is no space (or, more specifically, freedom) for alternative religious voices to speak. Subsequently, what we have is an image of Islam as a religion that is based on blind faith in a higher power that defines martyrdom through murder and self-sacrifice, that causes a whole nation to fall into a state of murderous chaos. The dialogue that Charlie Hebdo‘s work is meant to promote is, ultimately, shut down because this dominant narrative continues to prevail.

I’m reminded here of a line in Anne Frank’s diary that has stayed with me since the first time I read it: “In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart”. I believe that these words are ones that hold true for the concept of religion as a whole. The words of Jesus, Moses and, indeed, the Prophet Mohammed are ones that remain good, that have something relevant to say to the world. However, to engage with these words, there needs to be a shift in discourse, an understanding that the term “religion” as a whole is loaded with multiple meanings. We have to give the other voices the freedom to speak.

Reblogged this on Daily Observation and commented:

Agree

I think a closer look at some of those words is needed before we endorse them as good. Instructions to beat an unsubmissive wife or to regard women as inferior to men do not strike me as good.